Grosvenor Arch Milky Way Pano. Nikon Z 6II with an Irix 15mm f/2.4 Firefly lens and FTZ Adapter, mounted on a Novoflex VR-System Slim Panorama System, lit with two Luxli Fiddle LED panels. Eight frames shot at 15 seconds, f/3.2, ISO 12,800 and stitched in PTGUI Pro.

The Location

One standout feature among many in the nearly 2 million acres of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is Grosvenor Arch.

This hulking double sandstone arch stands 150 feet above ground. Named in honor of Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor (1875-1966), the first full-time editor of National Geographic magazine and husband of Elise May Bell, daughter of Alexander Graham Bell. Gilbert is credited with transforming the much-too-scholarly National Geographic into the illustrated and superb publication many of us have enjoyed for decades.

Figure 1. Grosvenor Arch sits in the backcountry of Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, which is gigantic. Click here to download a map of the area. Satellite imagery courtesy of Google Earth.

Photographers from the National Geographic Society named the arch after Grosvenor during a 1949 expedition, as they believed he “had done more than any other person to arouse public interest in geography.” So this was a fitting subject for Gabe Biderman and I to stop at during our 3-week tour of California, Utah and Arizona in 2021.

From our base in Kanab, Utah, Gabe and I made a day and night of driving north and past the entrance to Bryce Canyon (gasp!) and onward to Kodachrome Basin State Park for sunset (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nikon Z 6 with a Venus Optics Laowa 15mm f/2 FE Zero-D lens, mounted on a Novoflex VR-System Slim Panorama System. Seventeen frames shot at 1/60, f/8, ISO 100 and stitched in PTGUI Pro.

A fun detour! But our real goal for the night lay farther down the primitive, hardpack Cottonwood-Canyon Road.

Upon arrival, we noted that 1) only one other car was present and the owner was either sleeping or hiking, and 2) there was a bathroom. Yay! The ample parking and paved walkway were welcoming after some of the back-trail adventures we’d had.

While scouting (Figure 3), I knew that my ultimate goal was the rise of the Milky Way core and the resulting arch connecting with the landform. Gabe and I studied the scene and planned the compositions. I was really into making panoramas during that trip (and still am!).

Figure 3. Scouting with PhotoPills.

The Pre-Shoot Shoot

As darkness drew upon us, we still had a long time to go before the galactic core appeared. Not ones to waste a good dark sky, we shot plenty while waiting.

We started with deploying some Low-level Landscape Lighting (LLL). Gabe hiked down the road a bit and then a little into the field to set up a Luxli Fiddle LED panel. Being over one-third of a mile from the arch, Gabe turned it on at 30 percent brightness. The result was a crisp, directional light source that defined the most important shapes and textures of the eroding rock formation.

We set up 1.5-hour star trail stack (Figure 4) and dove hungrily into our sandwiches.

Figure 4. Nikon Z 6II with a Nikon Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S lens at 34mm. Sky: 31 frames shot at 4 minutes, f/2.8, ISO 800 and stacked in Photoshop; foreground shot at 8 minutes, f/4, ISO 800.

After sitting back and enjoying the stars for a bit, we moved closer to the arch to shoot some star-point stacks, while the clock crept ever closer to the triumphant rise of the galactic center.

During that time I made this composite image with a 15-image star point sequence and a longer base image for the landscape (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Nikon Z 6II with a Venus Optics Laowa 15mm f/2 FE Zero-D lens. Sky: 15 frames shots at 10 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 12,800 and stacked in Starry Landscape Stacker. Foreground: 8 minutes, f/4, ISO 800. Blended in Photoshop.

Reviewing those images in the field, I noticed that the ground was dark in the composition. As natural as that was, Gabe and I agreed to draw out some more definition in the trees closest to us. We set up much closer to the foot of the arch to put even more of it above the horizon. Having that air around the formation really brought out the space between the eroded, airy portions, not to mention set the stage for a landing point when the Milky Way would appear.

The Shoot

It was dark. Really dark. Bortle Class 1 dark (Figure 6). So our short exposures were shot at ISO 12,800, and for star points we were using NPF settings (see below), which made the exposure even more challenging.

Figure 6. Bortle Class 1 info for the Grosvenor Arch area. Source: lightpollutionmap.info.

As we began setting up the panorama sweep, we set another Luxli Fiddle in the two trees in front of us. The concept was to cast shadows toward our lenses and radiating outward toward the arch. This gave the otherwise dull and dark trees shape and texture.

I placed and leveled my Novoflex TrioPod Pro75, then mounted my VR-System Slim Multi-Row Panorama System. This setup gives me reliable and repeatable rotations. Repeatability was necessary because I planned to execute the pano sweep three times with different settings. (Though I did end up getting it in one pass—lucky!)

I chose the Irix 15mm lens for this shot. NPF exposure duration for that lens on my Nikon Z 6 is 18.04 seconds for Default and 9.02 seconds for Accurate (Figure 7). (See the post “NPF: The New Rule for Shooting the Sharpest Stars in the Sky” for further information.) I was already at ISO 12,800 and didn’t want to push further. I opted for an educated guess of 15 seconds to drink in as much light as I could. I felt comfortable leaning toward letting in more light in the near-darkness versus a “correct” exposure with little information to post-process.

Figure 7.

After test shots, I waited for the Milky Way to be in the ideal position, and then I committed and shot the sequence. Job done! Well … almost.

The Processing

In Lightroom Classic, I first made basic local adjustments. Then I processed one of the image sets (Figure 8) by adding a mask for the sky using the new AI-assisted Masking tool. I also brushed in the negative space under the arch and cleaned up some of the land/sky mask using the Subtract tool. I adjusted to taste for an ideal sky.

Figure 8.

Then I created another mask using Select Sky (Figure 9), and I inverted that to mask the landscape instead. Again I cooked to taste, being extra careful not to over-boost the shadows and accentuate the noise in them.

I also got rid of sky junk, of which I found a surprising amount (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Once I got my adjustments down, I synchronized them across all the images. (Note: When you have one of the new AI-created masks and you sync it across images, you have to go in and recalculate each of them. Adobe, are you listening?)

After confirming that each of the eight pano images was processed correctly, I used the Export to PTGUI menu command and chose TIFFs with Lightroom Adjustments.

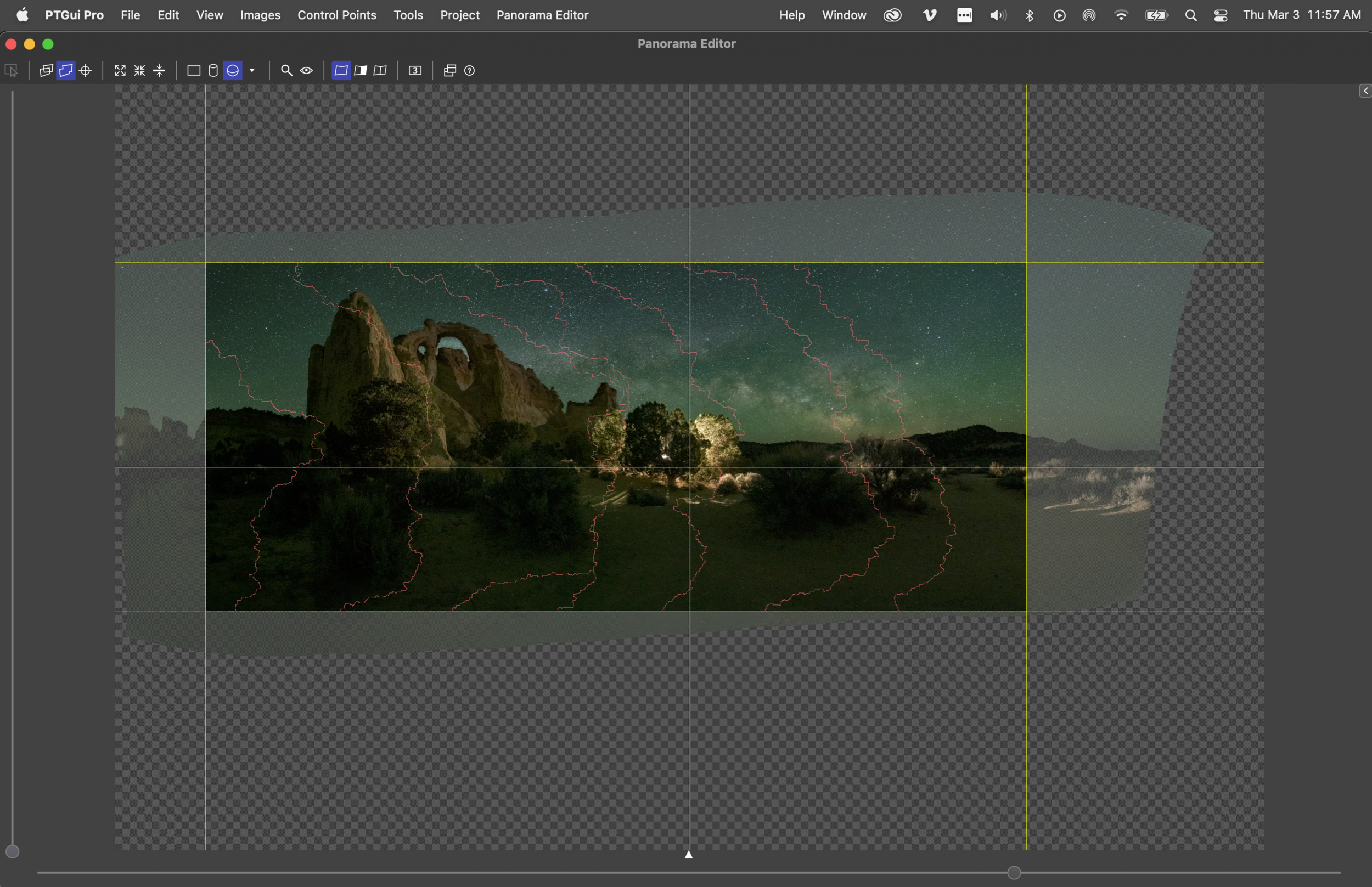

In PTGUI Pro, I moved through many of the different projections, looking for one that provided an ideal, natural perspective.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

I ended up with Equirectangular (Figure 11) and reduced the field of view to 270 degrees (Figure 12). A final step in PTGUI was to drag in crop lines from each edge for a final composition (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

I exported from PTGUI to the same folder as the raw files, then synchronized the folder in Lightroom Classic to get that final image back into my catalog. Then I studied the image one last time. I noticed the trees in the foreground got bright again, despite careful processing before stitching, so I brushed in a local exposure reduction (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Then it was time to make a final crop. I feel that the classic 3:1 ratio is perfect for this photo (Figure 15). It balances all the important elements in the scene.

Figure 15.

Wrapping Up

I find the final image (Figure 16) very true to the planning and preparation that went into this.

Figure 16. Nikon Z 6II with an Irix 15mm f/2.4 Firefly lens and FTZ Adapter, mounted on a Novoflex VR-System Slim Panorama System, lit with two Luxli Fiddle LED panels. Eight frames shot at 15 seconds, f/3.2, ISO 12,800 and stitched in PTGUI Pro.

It always pays to know when your celestial objects are going to be in the right place. PhotoPills was crucial in planning this from the hotel in Kanab.

What’s also essential is to look at a scene and have a bunch of other “tools in your toolbelt.” In this case, I was laser-focused on making a pano with the Milky Way arch, but it wasn’t the only photo I made that night. I made star trails, star point stacks and even a vertorama (not included here).

Making other photos while waiting on your dream image is the right way to warm up and to work out the kinks in any scene.

I hope you enjoyed coming along with me to one of the jewels in the crown of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Seize the night!

Further Learning

If you want to learn more about planning with PhotoPills, sign up for the waitlist for our PhotoPills Bootcamp: Bryce Canyon and be sure to get on our mailing list, as we’re sure to offer more PhotoPills workshops in the future.

If you want to shoot scenes like this under the amazing dark skies of the Kanab area, another outstanding opportunity to learn more about astro-landscape photography is by joining the outstanding group of instructors at the 2022 Nightscaper Conference April 26-29. Limited early bird tickets are available now.

Just for fun.