If you’ve been paying attention, you may have noticed that it’s gotten much cooler at night in recent years––about 3000 degrees cooler!

The nighttime world has transitioned from one that was overwhelmingly lit by yellow-orange sodium vapor lamps to one lit primarily by daylight-balanced LEDs. It’s happened quickly and it’s had a huge impact on night photography, especially in urban areas. Even night photography in national parks is impacted, as the distant glow on the horizon shifts from orange to white.

While there’s no doubt that LED lighting is more energy-efficient, and generally easier on the eyes, it is making for much more mundane and ordinary-looking night photographs.

Figure 1. Trona Pinnacles, California. November 2014. Canon 5D Mark II with a Nikon PC Nikkor 28mm f/3.5 lens. 30 seconds, f/8, ISO 6400. White balance: tungsten. Foreground lighting with a Four Sevens Quark 123 LED flashlight. Sky glow from mostly sodium vapor lights in the nearby small city of Ridgecrest.

Back in the 1990s I was living in San Francisco, and much of my night photography was done in and around industrial sites in the Bay Area. My friend Tom Paiva and I explored the abandoned piers along the Third Street corridor in the south of San Francisco, and the Southern Pacific rail yards across the Bay Bridge in Oakland. We were drawn to the strange machinery and architecture of these sites, but most of all it was the odd mixture of high and low pressure sodium vapor, mercury vapor and metal halide lights that we found so irresistible. We sought scenes lit with multiple light sources that created surreal colors when combined with long exposures on our film (Figure 2). These were exactly the kind of situations that I tried hard to avoid or to correct for in my commercial architectural work.

And there’s the rub––mixed lighting can be both a curse and a blessing depending on the situation at hand. To the artist, it makes for worlds of possibilities, and to the commercial photographer concerned with color accuracy, nothing but headaches.

Figure 2. Petaluma, circa 1994. Shot on Fuji NPL color negative film (tungsten), exposure unrecorded. A combination of sodium and mercury vapor lights illuminates separate parts of this image making for areas with radically different color balances—not to mention that crazy purple sky. Note the light on either side of the pole in the foreground.

Photographing mixed-lighting scenes with digital cameras and adjusting the white balance in post-processing allows for great flexibility in how an image is presented, and in turn the feelings or moods it elicits. We have it easy today being able to fine-tune (or even dramatically shift) the white balance after an image is made, and local adjustments make it even easier to “correct” for different colored light sources in the same frame.

Not too long ago that would have been an unimaginable luxury. Back in the days of 4x5 transparency film, I shot assignments where I would have to make multiple exposures on the same sheet of film for each light source. Testing was required to find the right filtration to put in front of the lens for fluorescent, incandescent, sodium, halide and other light sources, and if daylight was involved, windows would often have to be blacked out and then exposed for separately with all of the other light sources turned off. All of this had to be done while making sure the camera didn’t move between exposures. The gas discharge lamps often took 5 to 10 minutes to warm up after being turned off, so testing and exposing Polaroids and film might have taken 2 or 3 hours for a single image. In some instances, I could filter the lights directly and make a single exposure, but putting filter sleeves on a sea of fluorescent tubes in a large office space wasn’t much fun either. This is what it was like in the days before digital photography and even Photoshop.

But, back to our future …

In the images below of an old textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, the overall scene is lit with high pressure sodium vapor lights, and there’s a metal halide light out of sight behind the building on the right side of the frame. The interior is lit with either incandescent or possibly more sodium vapor lights.

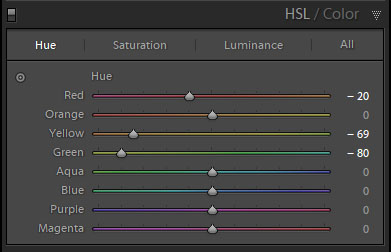

In each version, I’ve set the white balance differently by using Lightroom’s eyedropper tool to click on an area lit by one of the light sources. As is usually the case, my preferred white balance is somewhere between the neutral points used in the first two examples. After using the eyedropper tool to check various white balances (Figures 3a and 3b), I pick the one that is closest to what I want and then use the temperature and tint sliders to further refine the color (Figure 3c). In this kind of situation, the “right” white balance is the one that looks best, not a perfectly neutral setting.

Figure 3a: Pawtucket Textile Mill. December 2015. Nikon D750 with a Nikon PC Nikkor 28mm f/3.5 lens. 10 seconds, f/8, ISO 400. White balance neutralizing the metal halide light: 3100 K, +15 Magenta.

Figure 3b: The same image with the white balance neutralizing the sodium vapor light: 2050 K, +4 Magenta.

Figure 3c: The same image with the white balance set to personal taste: 2450 K, +7 Magenta.

Figure 4: An LED streetlight casting multiple shadows in Los Angeles, December 2013.

LEDs in the Modern World

In my recent travels, I’ve noticed that in both large cities and small towns around the country, most places have almost fully transitioned to LED lighting within the last 2 or 3 years. Lighting technology has evolved quickly, and early adapters—such as the city of Los Angeles (Figure 4), which converted to LED in 2012 and 2013—now find themselves with outdated fixtures that use multiple diodes and cast weird repeating shadows. Newer lights are brighter, and don’t require multiple diodes for adequate brightness. Even my tiny hometown of Hinesburg, Vermont, has completely transitioned to LED streetlights, casting the town in a naturalistic—but boring—neutral glow.

I had the great fortune to lead National Parks at Night’s Easter Island and Morocco photo tours this winter, and observed that relatively poor and extremely remote Easter Island (Figure 6) has converted to LED lighting, but Morocco, which generally has better infrastructure, is still lit mostly by sodium vapor. Granted, there’s only one town on Easter Island, while Morocco (Figure 5) is a country that is slightly larger than California with several major cities! I guess it’s not a fair comparison, but it was interesting to see. I haven’t been to Cuba since 2015, but I’m guessing that when Gabe returns next week, he’ll report that Havana still glows orange at night!

Figure 5. Essaouira, Morocco. March 2019. Nikon D750 with a Nikon PC Nikkor 28mm f/3.5 lens. 13 seconds, f/11, ISO 100. White balance was set to auto, which used 4350 K, +36 Magenta. I adjusted it to 3950 K, +37 Magenta by clicking the eyedropper tool just above the archway in the foreground. The orange light is high pressure sodium vapor, the green is from mercury vapor, and the archway was lit by either metal halide or LED. The window in the tower is most likely an LED bulb.

Have you noticed the Color of Night in your town lately? Has it changed, and if so, was it for better or worse? Let us know in the comments below or on our Facebook page.

Figure 6: Tahai, Rapa Nui. February 2019. Nikon D750 with a Sigma 24mm f/1.4 lens. 20 seconds, f/2.2, ISO 3200. White balance was set to auto, recorded as 3550 K, +2 Magenta, and adjusted to 3300 K, +6 Magenta. Six vertical images, merged to panorama in Adobe Lightroom. The Moai at Tahai are just at the edge of Hanga Roa, the only town on Rapa Nui, or Easter Island. They are the only Moai that are (indirectly) lit by artificial light, and one of them told me that they were not pleased at being lit up all night every night. Most of the light in this scene is from LED street lighting, but there is one sodium light casting a yellow tinge on the right side of the image. The rock platform in the foreground on the left was lit with a Luxli Viola set at 3200 K.