As you might imagine, we get emails from time to time asking us questions about night photography. We’re always happy to respond personally to those questions. However, there’s also the (largely correct) theory that for every person who asks a question, there are a hundred others who want to know the same thing but didn’t ask.

Therefore, we have decided that from time to time we will collect five of the questions that have recently been asked of us, and share them, along with our answers, with all of our blog readers. We hereby commence this “Five Questions” series today.

Our first foray into shedding some light on night photography conundrums includes some excellent questions on gear, techniques and etiquette.

1. SharpStar2 and the Nikon 14-24mm

Q: I have the Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens. I have just finished reading about the SharpStar2. In my very limited experience with photographing stars, I have yet to obtain anything close to a sharp focus on them. Thus I’m intrigued by the SharpStar2. Can this be used with the lens I’ve mentioned? I’m assuming I would have to purchase the appropriate square filter holder and the appropriate size SharpStar 2 filter. Could you tell me what size to order, and which filter holder you’d recommend? — Liela N.

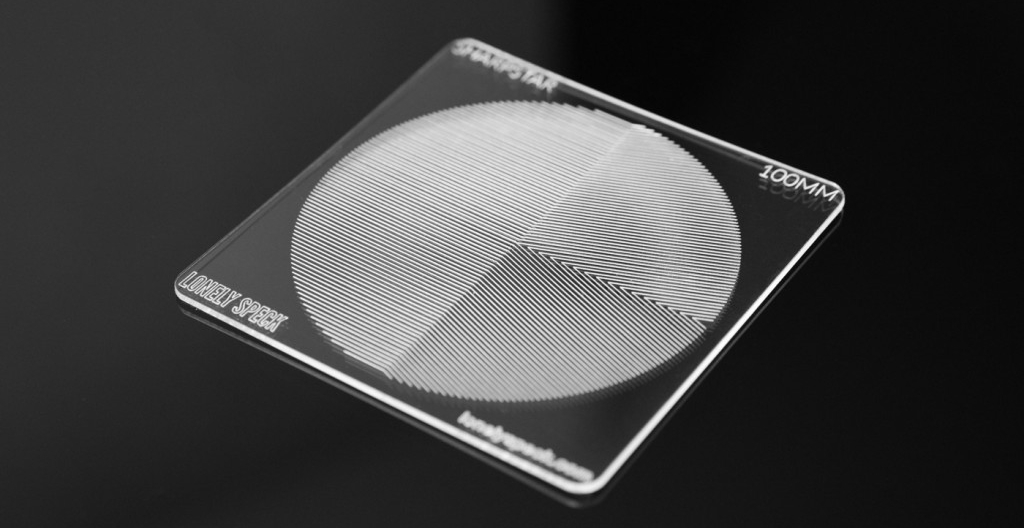

A: Although the Nikon 14-24mm is one of the best lenses for night photography, it’s actually not one I can recommend for combining with the SharpStar2. In fact, I’m not sure there’s a way to get it to work at all. The issue is that lens has the bulbous front element, which means a flat filter can’t be used without retrofitting a holder. There’s a great article on Naturescapes titled “Adapting Filters to Fit the Nikon 14-24mm Lens” that explains why and offers a DIY solution, but it requires a 150mm filter, and the largest that SharpStar2 comes in is 100mm.

But I would definitely hold on to that lens for night photography! If you’d like to work on other techniques for focusing in darkness, I’ll offer three suggestions:

- Use Live View. It’s infinitely easier than trying to focus through your viewfinder.

- Try presetting your lens to infinity during daylight, then turn off autofocus and tape down the focus ring.

- Use hyperfocal distance.

Incidentally, if you’re interested in purchasing the SharpStar2 for other lenses, we have a discount code we can share with you. Use “NPAN10” to receive 10 percent off the SharpStar2 on LonelySpeck.com. — Chris

2. Stack-a-Matic

Q: I use Photoshop/Lightroom CS6. I am a new user to Photoshop so obviously still learning. I tried to download your recommended Stack-A-Matic but I get an error that says I need Photoshop 12 or higher. What is a good stacking program that goes with CS6? — Sue W.

A: Stack-a-Matic works with CS5 thru CC (latest). Did you download it from my website, and use the manual installation instructions? Sometimes it’s a little bit finicky, but it does work. You might have to do a restart, or possibly walk through the installation twice, but it’s worth it.

I’m sorry that I can’t offer more tech support than this for Stack-a-Matic; I’m just hosting it for Russell Brown. Alternatively, you can try StarStax for Mac, and Startrails.exe for PC. — Lance

3. Light painting in Arches National Park

Arches National Park. © 2016 Tim Cooper.

Q: I heard/read that Arches National Park has closed the permits for night photography. Does this mean for workshops or personal? — Juan Aguilera

A: Yes, Arches (and Canyonlands National Park) did institute a rule change this year, but it applies only to instructor-led groups using an official CUA (Commercial Use Authorization) permit, and for the moment it applies only to light painting.

If you go on your own as a photographer, there are no restrictions—for now. But if photographers don’t collectively respect that environment (i.e., behave ourselves), who knows what might change? While we don’t agree with a blanket rule change in Arches, we do understand why it was implemented. We always talk about the etiquette of doing night photography in a way that doesn’t negatively affect others who are enjoying the same dark skies that we’re photographing. (See the early sections of the “Night Photography in National Parks” presentation Lance and Chris did at the B&H Event Space a few months ago.)

However, it’s also good to note that if you’re planning to shoot in Arches in 2017, the park will be closed at night every Sunday through Thursday due to road construction. So you can do night photography only on Fridays and Saturdays, until the expected November completion date. — Matt

4. Aurora in New England?

Q: Is there any chance of seeing aurora in New England? And is there a good app that you use for potential activity? — HersheyArtImages

A: The aurora can occasionally be seen in southern New England, but it is usually just a little bit of green near the horizon in the northern sky, when seen from a dark beach with a view to the north. In the northern parts of Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine, it is seen a little more frequently.

We use an app called Aurora Forecast, which is available for both iOS and Android. Once you download it, you can customize the settings to send you an alert for a kp (the unit of measurement of auroral activity) of 6 or higher in the middle latitudes. If the activity is much less than that, you are not likely to see anything.

You will never see aurora from a light-polluted area so far south. Really strong displays can sometimes be viewed right in the center of Reykjavik –– but that is a much smaller city, with much smaller suburbs. — Lance

5. Dealing with light pollution

In this photo from Everglades National Park, light pollution from distant Miami builds up in a 30-second exposure to provide depth to the scene. © 2013 Chris Nicholson.

Q: I am struggling with processing wide-field astrophotography images (starscapes, Milky Way, etc.). In particular, with how to remove light pollution, which is an unfortunate fact of life for those of us living in the eastern part of the country. For wide-field photographs, the light pollution is usually graduated over the image, being brightest at the horizon and diminishing at you go higher. I would very much appreciate any tips you might have in this area. — David T.

A: Honestly, I generally don’t do anything to try to rid light pollution from my night photos, but rather try to use that extraneous light creatively. Specifically, I use the distant light to create silhouettes of mountains, for example, or to light clouds in the sky. Both of those tactics can provide depth to otherwise pitch-dark scenes.

If you do want to negate the color effect of light pollution in the night sky, a tech option is to try one of the new filters for eliminating the color cast in the sky that can be caused by light pollution. Our friends at Lonely Speck recently released the PureNight filter, which is made from a special didymium glass that reduces the transmission of light from sodium vapor lamps. We have yet to try it, but they know their stuff, so it’s likely an excellent solution. We also just heard about the NiSi Natural Night Filter from Ikan, but again, we haven’t had the pleasure of trying it yet. — Chris