If you have questions, we have either answers or opinions, and we’re not shy to share either.

This installment of our “Five Questions” series features inquiries about Adobe’s new Super Resolution, the work of Alexey Titarenko, Milky Way lenses for the Nikon Z 7, intervalometer recommendations, and the efficacy of carrying two Coast flashlights.

If you have any questions you would like to throw our way, please contact us anytime. Questions could be about gear, national parks and other photo locations, post-processing techniques, field etiquette, or anything else related to night photography. #SeizeTheNight!

1. Seeing Quadruple

Question:

Regarding your post about Adobe’s new Super Resolution feature, I was surprised to see the headline mention “quadruple” enlargements. I thought the new feature was “2X.” Did I read it wrong or misunderstand the feature announcement? — Robyn

Answer:

It’s just a math thing. You are correct that Super Resolution doubles the pixel count of an image in both the horizontal and vertical linear directions. For example, a 200 x 300 image would become 400 x 600.

That results in the total area of the image being quadrupled. In that same example, the resolution would go from 60,000 square pixels to 240,000 square pixels—i.e., quadruple, or four times the number of pixels. See the image above for a graphical representation. — Chris

2. Ghosts in the Composition

Question:

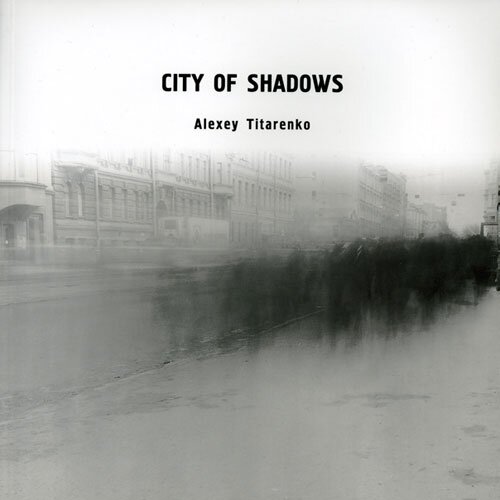

I am trying to mimic Alexey Titarenko’s work, especially the movement he puts in. I used native ISO, an appropriate aperture and a long shutter. Would you mind giving me help in this type of work? — David C.

Answer:

I assume you are talking about Alexey’s “City of Shadows” series. Interesting human movement happens in exposures from 1/15 to 15 seconds, because most people can’t hold truly still for more than 1 to 2 seconds.

In order to create the “ghosts and shadows” effect that Alexey is getting during daytime, you need to use a 3-, 6- or 10-stop neutral density filter to allow for a long enough exposure. Operating under overcast skies will help, as will lots of experimentation.

A lot depends on how much stillness you want to show in the chaos of movement. That is important. For example, for Alexey’s shot of the handrail, it was critical that the rail remain sharp amid the mass of bodies moving past. It works beautifully. However, many of his other photographs feature just a little movement, which allows him to capture a “soul” that is still.

On the other hand, reaching longish shutter speeds like that at night is easy, because you’re already working with minimal light. In fact, the challenge in dark conditions is actually adding light so you can see the human subjects in all that darkness. For more info on how to do that, see my blog post “Photographing Phantoms.” — Gabe

3. Z 7 Milky Way Glass

Question:

I have a Nikon Z 7 and would like to try Milky Way photography this summer. I have the Nikon Z 14-30mm f/4 S lens and believe the f/4 aperture will not be fast enough to prevent star streaking. Would the Nikon Z 20mm f/1.8 S or the Irix 15mm f/2.4 be an acceptable alternative? — Jerry

Answer:

You’re right that the f/4 lens will be very limiting for star-point images in general. They would require you to shoot at an ISO of 12,800, which I would not recommend with the Z 7 unless you’re planning to stack multiple frames in software such as Sequator or Starry Landscape Stacker. Since you have a Z 7, I suggest going with a native Z lens. Though I haven’t shot with most of them, word is that they’re all truly outstanding.

I have not shot with the Z 20mm f/1.8, but I love that focal length for Milky Way. So I think that either that lens or the more-expensive Nikon Z 14-24mm f/2.8 would be your best bets.

The Irix lenses are excellent, though they require an adapter to use on a Z-mount camera. (Irix will no doubt release Z-mount lenses in the future, but we don’t know how near that future is.)

If you’re still stuck about which lens to buy, you could always rent to try before committing. We can recommend Borrow Lenses or Lens Rentals. — Lance

4. Intervalometer Recommendation

Question:

I just reviewed your 2017 article on wired versus wireless intervalometers. Are you still recommending the wired Vello Shutterboss II? — Hadley

Answer:

Yes, it’s still on the recommended list for wired intervalometers. Though it does share the one weak spot of all wired intervalometers, which is the connection point to the unit, which often wears down over time.

If you’re open to a wireless solution instead, my favorite intervalometer overall is the Phottix Aion. Not only does it not suffer from that weak spot, but it also allows for exposures of fractions of seconds, which is useful when shooting with NPF Rule shutter speeds.

To learn more about the Aion, see my post “A Better Intervalometer.”

Though I do champion my favorite, either of the above options will suffice. You really can decide based on your personal priorities and be happy and successful either way. — Matt

5. Are Two Coasts Better Than One?

Serpent—Borrego Springs. Nikon D4s with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens set at 24mm, light painted at close range with a Coast HP7R flashlight. Three exposures at 15 seconds, f/4, ISO 6400.

Question:

I notice that you guys seem to all have both Coast HP7R and HP5R flashlights. I want to buy a more powerful small flashlight than I have now. Do you own both because the HP7R is too powerful for some applications? If you were to buy just one, which would it be? — Mark

Answer:

Yes, we all own both the HP7R and the HP5R because the difference in power is useful for different applications. The HP7R is a very bright flashlight (300 lumens), while the HP5R is less bright (185 lumens). Both have a second power setting that drops the output by 90 percent, so the combination essentially gives us four different lumen options.

How do we use this versatility? One example: If we’re shooting the Milky Way under a new moon (pitch black, no moonlight at all), then our apertures are very wide (f/2 or f/2.8) and we are using very sensitive ISOs such as 3200 or 6400. That makes 300 lumens overkill and more difficult to control, whereas 185 lumens can be very effective. You just don’t need a powerful flashlight for that kind of sensitive exposure.

An opposite example is when we’re shooting under the much brighter conditions of a full moon, when our apertures may be set to f/5.6 or f/8 and the ISOs to 100 or 200. These less-sensitive exposures require a stronger flashlight to paint the scene.

The different flashlights can also be more or less useful when considering the distance of the subject from where you’re light painting. A rock formation 100 yards away obviously requires a more powerful light than a flower 2 feet in front of you.

So yes, it’s nice to have both models to cover all the possible situations. But if you are looking to purchase just one, I would recommend one of these strategies:

Purchase the more powerful HP7R and use some neutral density gels to knock down the power when needed. You can get a sample pack that contains all you might need for less than $10. Remember, you can always make a bright flashlight dimmer, but you can’t make a dim flashlight brighter.

Decide which conditions you favor for night photography. If you mostly shoot under a new moon, get the HP5R. If you find yourself doing a lot of work under brighter conditions (full moon, city scenes), purchase the HP7R.

Either way, both of these Coast flashlights are excellent night photography tools that are worth every dollar you spend on them. — Tim