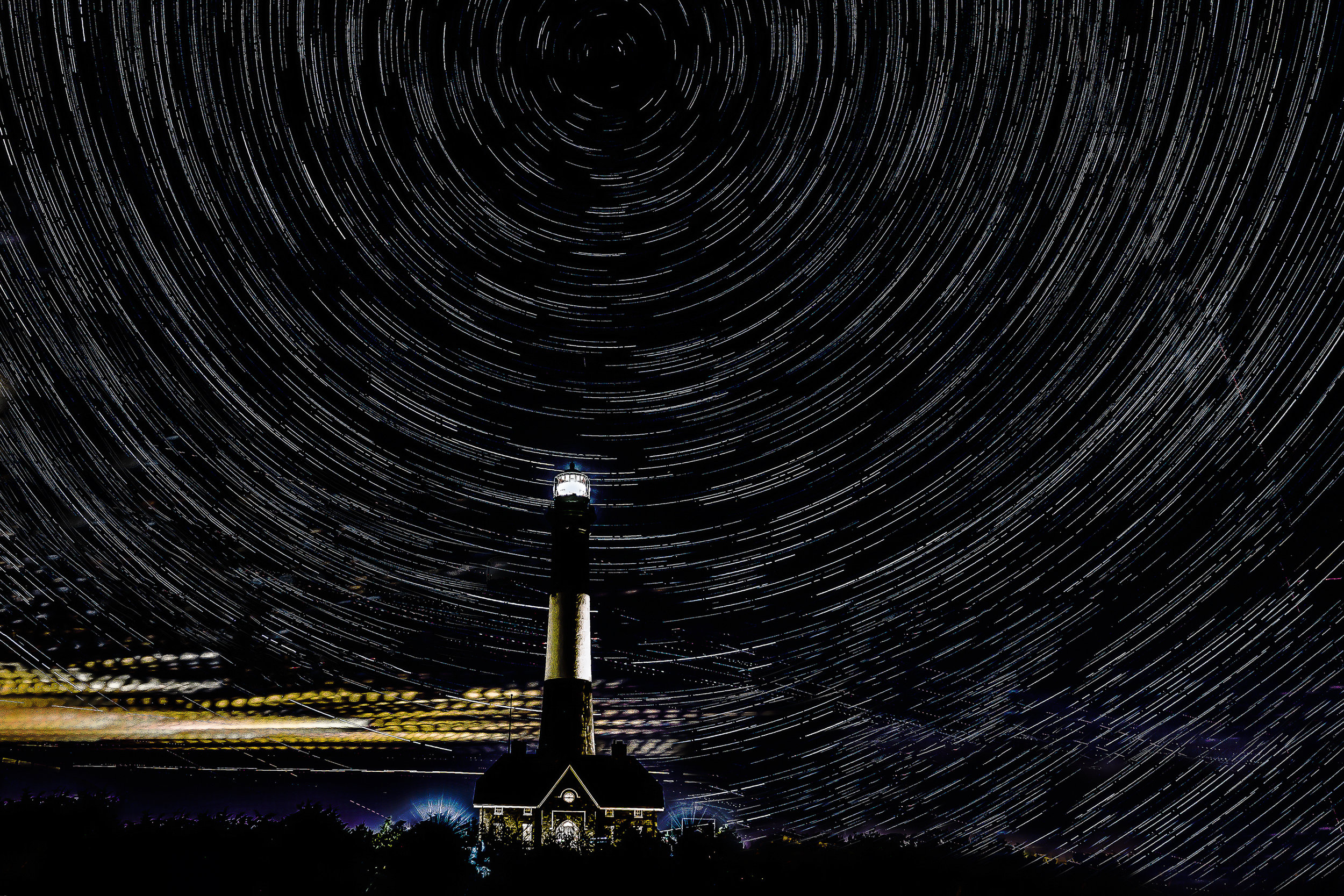

Looking across Cinder Cone to the Milky Way, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter. © 2018 Lance Keimig.

Last summer Chris and I had a chance to spend a few days in Lassen Volcanic National Park in Northern California. Lassen is one of the least known and least visited parks in the West, but it had been on both our radars for a long time. As the more popular parks like Joshua Tree and Yosemite become increasingly crowded, hidden jewels like Lassen Volcanic provide tremendous opportunities for photographers––or for anyone who wants to explore the wonder of our public lands without being overwhelmed by other tourists.

Lassen peak from Cinder Cone at Sunset. iPhone 6S+.

The Location

Roughly an hour east of Redding, California, Lassen is remote and far from the state’s major cities, which probably explains its relative obscurity. It certainly isn’t because the park doesn’t have much to offer—quite the contrary. In some ways, the park typifies the High Sierra landscape: rocky, mountainous terrain, rivers, lakes, wildlife, fragrant Jeffrey pines, hot days, cool nights, and clear, crisp air. Add some recently erupting volcanoes to the mix, and perhaps you can start to appreciate what makes this park special.

All four of the major types of volcano are present in the park. Lassen Peak, which the park is named after, is the southernmost active volcano in the Cascade Range. It is a lava dome, and is the largest of this type anywhere in the world. Lassen Peak last erupted between 1915 and 1918. The park also contains composite and shield volcanoes, as well as cinder cone. In today’s post, I’m going to write about the appropriately (if unimaginatively) named Cinder Cone volcano.

Cinder Cone from the Butte Lake Campground trailhead. iPhone 6S+.

Nestled in the northeast corner of the park, far from the main visitor center, accommodations and other infrastructure, many visitors to Lassen Volcanic never get to see Cinder Cone. It’s the youngest volcano in the park, formed only 350 years ago!

Getting to the top of the cone is one of the more challenging hikes in the park, but the solitude and the views of Lassen Peak, nearby Butte Lake and the Painted Dunes below are well worth the effort. Cinder Cone has a relatively rare feature in that it contains two concentric craters, making it twice as photogenic as your ordinary volcano!

Nikon D750, Irix 15mm f/2.4 lens. A 10-frame panorama. All exposures 8 seconds, f/3.2, ISO 100.

The Experience

We arrived late in the afternoon and made the 1.5-mile hike to the base of Cinder Cone from the trailhead at Butte Lake Campground. It was slow going, having to trudge through the forest over the loose, sandy volcanic soil, but when we rounded a bend and first saw the cone appear before us we quickened our pace at the excitement.

The sun was sinking quickly as we began our ascent. Chris was determined to get to the top before the sun set, and we were literally racing the shadow up the side of the mountain. It’s a testament to how challenging the climb was that the shadow was at many times moving faster than we were. During one of our frequent stops to catch our breath, Chris said that we were experiencing “Type 2 fun.” Apparently, misery that is remembered nostalgically is what makes for Type 2 fun. It’s only in hindsight that you realize you were having a good time. It was worth every minute of the effort, and I was happy to be sharing the experience with Chris as his determination to beat the sun to the top kept me going.

Type 2 Fun. Chris racing the sun to the top of Cinder Cone. Nikon D750, 24-120mm f/4 lens at 110mm. 1/60, f/7.1, ISO 100.

When we finally reached the summit, the scene before us was extraordinary. We were surrounded by an awesome panoramic view on all sides, staring across a 1,000-foot-wide double crater with Lassen Peak to the southwest, Butte Lake to the northeast, and the Painted Dunes to the south.

Our excitement led to newfound energies that had us circling the rim of both the outer and inner craters, but not quite enough energy or madness to descend into the inner crater, knowing we’d have to come back up at some point. The local terrain was spartan, with only a few trees and colorful low flowers dotting the landscape. We spent about an hour and a half alone on the summit, exploring, photographing and waiting for darkness.

The Painted Dunes at sunset from Cinder Cone. Nikon D750, 24-120mm f/4 lens at 34mm. 1/25 second, f/8, ISO 400.

The Night

We knew that once darkness set, we would have a spectacular view of the Milky Way, and that a rare planetary alignment we had witnessed earlier in the trip would present us with a unique opportunity to make a great image.

We were there in early July. Mars was approaching opposition, the point where Earth is exactly between our red neighbor and the Sun. Mars was approximately 40 million miles away from us, compared to its normal average distance of 140 million miles. It was five times brighter than usual and was the brightest object in the sky after the sun and moon. Jupiter and Saturn were not to be left out, as they had just passed their own oppositions.

All of this meant that if Earth was almost directly between the sun and planets, the planets would appear relatively close to each other in the sky. Of course, early July around the new moon is a great time to view the Milky Way too. The best time of year to view the galactic core is when it is at opposition. Can you guess where this is all headed?

“As astronomical twilight faded the scene before us made our hearts race with excitement. It was incredible.”

We positioned ourselves on the northwest side of the crater so that we could look across it to see the Milky Way and planets rise as the sky darkened. We had a pretty good idea of where the core and planets would appear based on experience and our previous nights photographing in the park. Despite having a good idea of what was coming, as astronomical twilight faded the scene before us made our hearts race with excitement. It was incredible.

As the objects in the night sky brightened, the landscape before us darkened dramatically, and we wondered if we would be able to capture both the crater in front of us and the celestial glory above. We were constrained by the requirement to keep our exposures short enough to maintain the stars as points rather than trails, aperture-limited by comatic aberration, and ISO-limited by high ISO noise.

Of course there are several ways to deal with the differing exposures for ground and sky in astro-landscape photography. One could compromise and have an underexposed foreground and an overexposed sky and make the best of it, or make separate exposures for each at different settings and combine them during post-processing. Because we are masochists, we decided to light paint the 1,000 feet of crater during our 20-second exposure.

The Shoot

Chris and I both follow a similar procedure when we make night photographs. Every image is made by following the same basic steps. They are:

compose

focus

calculate exposure

determine lighting

tweak and repeat

In this case, the composition was fairly straightforward. We knew we wanted the crater in the foreground and Milky Way above it. We aligned ourselves, and set up our cameras about 40 or 50 feet apart. Because the scene was so large, the distance between us made for only a slight variation in the foreground of our compositions.

A few test shots to get the lines right, and it was time to focus. I was using the Irix 15mm f/2.4 lens, which has a convenient and accurate detent at infinity. There was nothing closer than about 50 feet in my foreground, so I knew that I could safely focus at infinity without worrying about anything being soft. I rotated the lens until I felt the detent, and that was it for step 2.

On to exposure. There was no moon yet (it wouldn’t rise for another couple of hours), and only a little light pollution on the horizon from the resort towns surrounding Lake Almanor to the southeast. The standard astro-landscape (ALP) exposure of 20 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400 would be about right. I chose to close down one-third of a stop to f/3.2 because I wanted to minimize coma in the bright planets, which were close to the left and right edges of my frame. To compensate, I increased the shutter speed by one-third of a stop to 25 seconds, and made a test.

Test image looking across Cinder Cone to the Milky Way, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter. Nikon D750, Irix 15mm f/2.4 lens. 25 seconds, f/3.2, ISO 6400.

Every ALP exposure is a compromise. The Earth’s rotation limits shutter speed because of the need to maintain star points. The limit is based on sensor size, focal length and the cardinal direction your camera is facing. Increase your shutter speed, and risk star trails instead of points. Open up your aperture to maximum, and risk coma and softness at the edges of the frame, as well as potential depth of field issues with foreground objects. Raise your ISO and the noise increases, especially in the underexposed shadow area common in the foregrounds of ALP images. It’s up to the photographer to decide which variable to compromise based on experience, equipment, taste and how the final image will be displayed. But I digress—on to the lighting.

The final image. Looking across Cinder Cone to the Milky Way, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter. Nikon D750, Irix 15mm f/2.4 lens. 25 seconds, f.3.2, ISO 6400. Lighting with two Luxli Violas at 3200 K and 100 percent brightness for the entire exposure. Mars on the left, Jupiter on the right. Saturn is hard to make out because it is right in front of the galactic core.

We really didn’t know if it was going to work or not, but there was nothing else to do but try it. We both had Luxli Violas, and the same idea. Usually we set these lights at 1 percent brightness for ALP images, and sometimes even that is too much. We are not usually trying to light the better part of a square mile in 20 seconds.

We set the color temperature to 3200 K and the brightness to 100 percent, opened the shutters, and walked quickly away from the cameras holding the lights toward the crater but tilted upward so that the foregrounds would not be overly bright. The technique worked remarkably well, and after a few adjustments we felt like we had it in the bag.

Wrapping Up

As we approach Thanksgiving and I look back at the images I made this year, this may well be my favorite from 2018. It’s a unique photograph made in an amazing location, collaborating with a great friend. It took some determination to make it happen, along with the good fortune of being in the right place at the right time. #ISO6400andBeThere

Note: Lance will be back at Lassen Volcanic National Park, this time with Gabe, for our 2019 night photography workshop. Click here for more information.