“Clements Mountain, Star Trails, Waterfall.” © Tim Cooper.

The Location

I am fortunate to live in Montana. It’s a beautiful state filled with wonderful people and fantastic landscapes. My “backyard” is Glacier National Park. Glacier is truly one of America’s great alpine experiences—from gorgeous glaciated peaks to alpine meadows carpeted with wildflowers to the host of wildlife visible on a near daily basis. I take every chance I can to get up to the park.

Early last summer I made this image while scouting for our upcoming National Parks at Night workshops in August and September. (While the first week of this workshop is already filled, the second week still has some spots available. Check out our workshop page for more information.)

Luck vs. Planning

When it comes to photography, I always give luck a little credit. Did the clouds cover the sky? Or did they add a nice accent? Did it rain on the night I had planned to shoot? There are so many small blessings that are easy to overlook.

Luck, however, is no substitute for planning. If you read this blog often then you have seen us discuss many times the importance of planning a night shoot. My familiarity with Glacier helped enormously with planning this shot. I already knew the location of the waterfall and exactly where I wanted the moon to be so that it would backlight the water. It was just a simple matter of using the indispensable phone app, PhotoPills, to determine when the moon would reach the necessary spot in the sky (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The zoomed-out and zoomed-in views of the shoot location, as seen in PhotoPills’' Planner mode. The blue lines told me where the moon would be at different times of the night, which told me when to shoot for the effect I wanted.

The Exposure

I wanted to use the moon to illuminate the falls, but I also envisioned star trails rather than star points in my image. To create the effect of star trails, you have to make a very long exposure—15 minutes, 30 minutes, an hour or even longer. This makes the stars appear as if they are trailing through the sky. Another method to create these trails is to break up the exposure time into shorter chunks, and then stack the resulting set of images in post-production. This is especially helpful under bright moon situations or when you want to light paint.

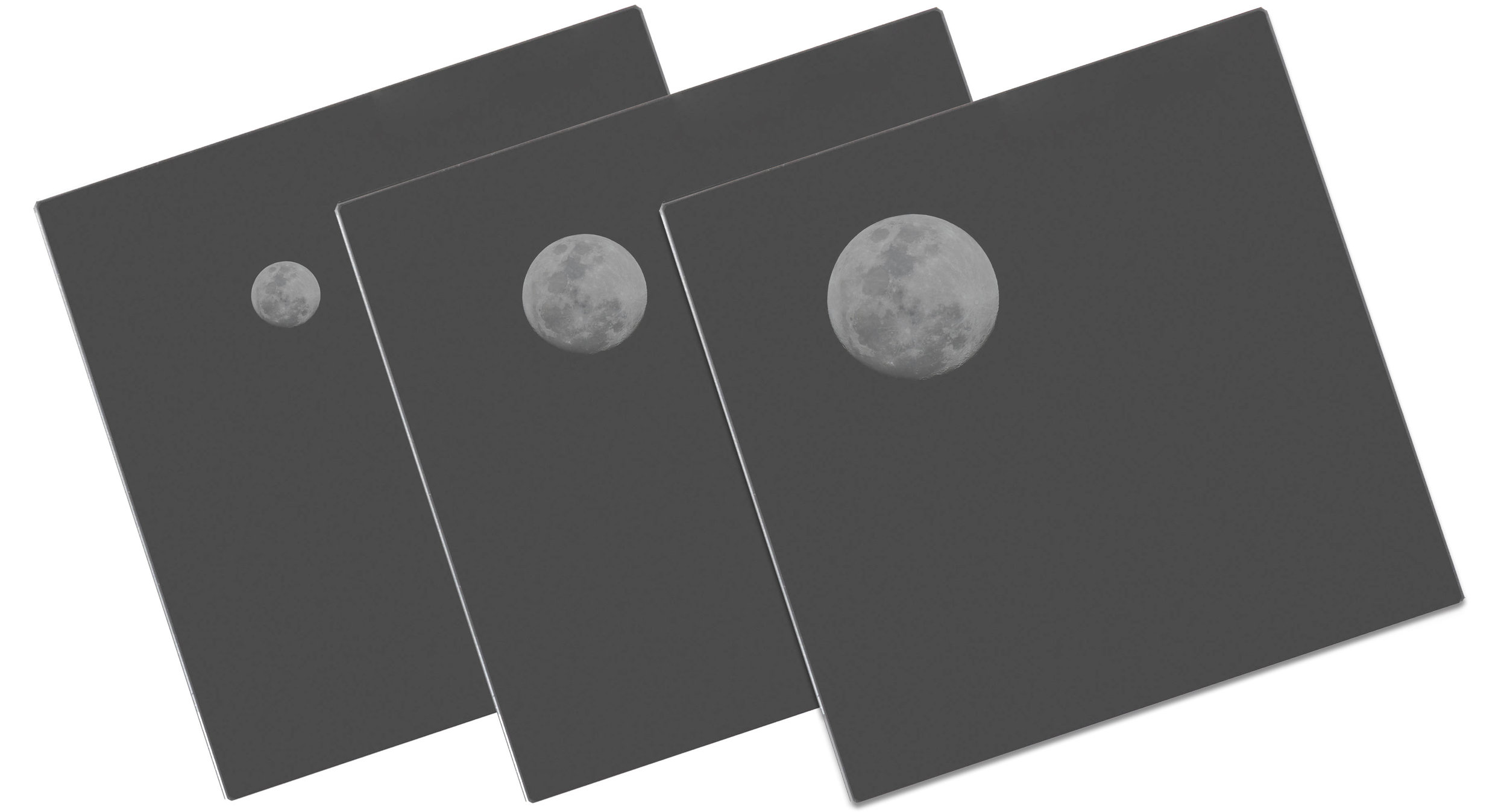

Using multiple short exposures was my plan for this setup. The first step was to calculate an exposure using a high ISO test (i.e., the 6 Stop Rule). Setting my Nikon D4s to ISO 3200 and f/4, my final test shot (Figure 2) was exposed for 30 seconds.

Figure 2. Test shot at 30 seconds, f/4, ISO 3200.

The Shoot

Typically night photographers use an ISO of 6400 for test shots because, according to that 6 Stop Rule, we know that an exposure time of X seconds at ISO 6400 equals X minutes at ISO 100. This is a very handy little trick for calculating long exposures easily.

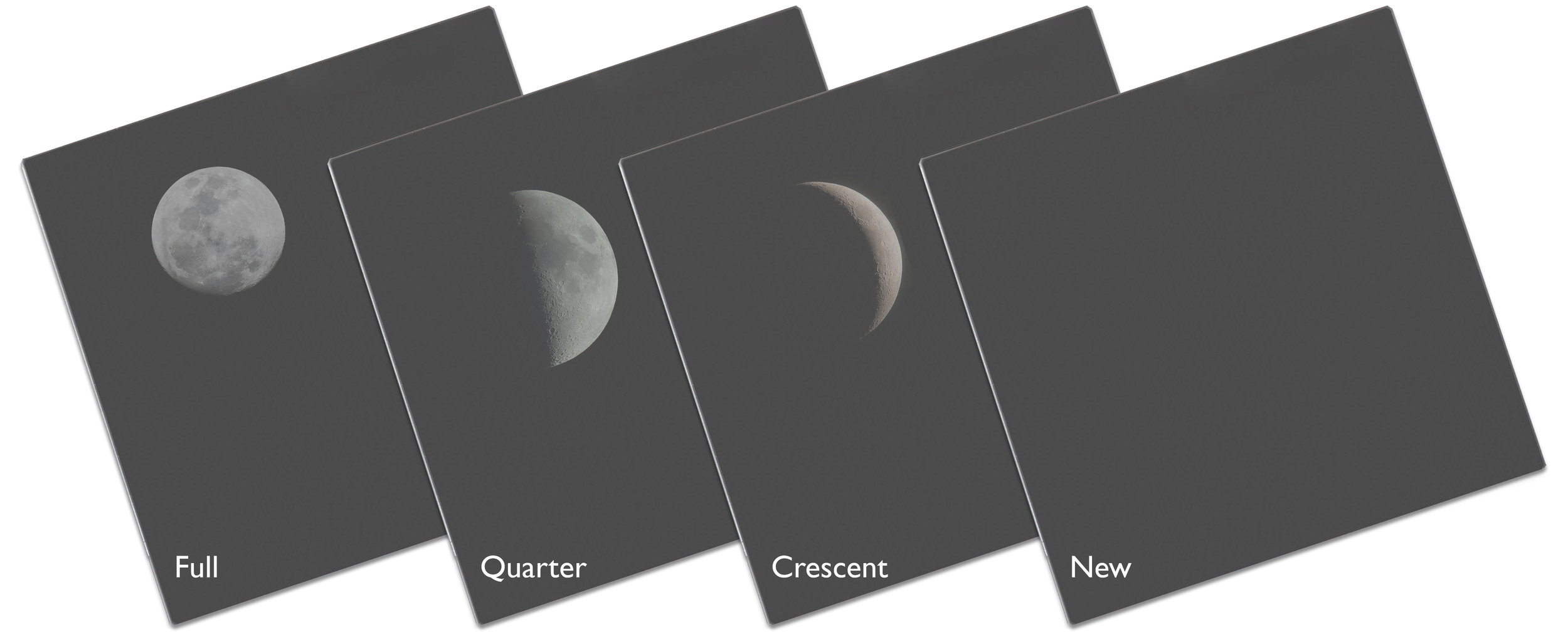

Because my successful test exposure was 30 seconds at ISO 3200, which equals 15 seconds at ISO 6400, then my long low-ISO exposure would be 15 minutes at ISO 100. Or—to shorten things up a bit—8 minutes at ISO 200. Using this exposure, I could shoot multiple frames at 8 minutes and blend them later in post using the star-stacking technique.

This evening, however, I either miscalculated or mistakenly set my camera wrong. My final exposures (Figure 3) ended up being shot at 5 minutes, f/4, ISO 100. That’s about two stops underexposed!

Figure 3.

I didn’t notice that at the time. I finished shooting and had to leave immediately, so there was no time to reshoot the frames. I was destined to have to fix it later in post.

Post-Processing

After downloading my images, the first post-processing edit was adjusting the Exposure slider to account for the underexposure out in the field. After increasing the exposure, the final set of images looked like this:

Figure 4.

The next step was to blend all the frames together to create the star trail effect. I began by selecting all of the images in Lightroom. Next, from the menu I selected Photo > Edit In > Open as Layers in Photoshop. This opens all of the images into Photoshop as layers within one file.

Once the file opened, I clicked on the top layer, held down the Shift key, then clicked on the bottom layer. This selects all of the layers in the file.

Next, in the Blending Mode drop-down list (circled in red in Figure 5), I selected Lighten (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

This blending mode allows the brightest part of each layer to show through on the final image, which in this case creates the effect of the stars trailing across the sky. Figure 7 shows the result of blending the images with this technique.

Figure 7.

Did you notice the multiple car headlights that showed up after blending the layers? They were in the first, second and last photo frames (Figure 8). Because using the Lighten mode reveals the brightest parts of each layer, all the headlights showed up after blending.

Figure 8.

So, the next step was to remove the unwanted car lights. One of the benefits of stacking frames rather than taking one long exposure is that you can use layer masks to remove unwanted artifacts that show up in just a few frames rather than overwhelming an entire final photo. To do this, I clicked on the first layer that contained headlights to select it. Then at the bottom of the Layers palette I clicked on the Add a Mask icon (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Next I selected the paintbrush tool and chose black as my foreground color. Then I just painted on the mask over the area I wanted to remove. Notice in Figure 10 how I painted over the tunnel where the car headlights appeared. Also notice the corresponding black area on the white mask thumbnail, indicating the shape and location of the mask.

I followed the same steps for the other two layers with the artifact, painting out the headlights further up the road. Figure 11 shows the three masks with black painted on them covering up all of the headlights that exist on the different layers.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

Finally, I wanted to separate the cool tones of the sky from the foreground waterfall. I clicked on the bottom layer, chose the Quick Select tool and then selected the foreground waterfall and cliff face (Figure 12).

Then I created a Color Balance layer by choosing Layer > New Adjustment Layer > Color Balance. Adding some warmth via the Red and Yellow sliders started to really separate the warm colors in the foreground from the cool colors of the background.

Figure 13 shows the final image.

Figure 13. Five stacked frames, each shot at 5 minutes, f/4, ISO 100 with a Nikon D4s and Nikkor 14-24mm f/2.8 lens zoomed out to 14mm.

While this may sound like a lot of work, after a little practice in Photoshop, you’ll find that completing these types of images takes no time at all!